Magnesium for Athletes: Effects, Needs, and Supplementation Scientifically Explained

Magnesium is an essential mineral and cofactor in over 300 enzymatic reactions in the human body. It plays a central role in processes such as energy metabolism, muscle and nerve function, bone health, and the regulation of the cardiovascular system (1). Nevertheless, this does not automatically mean that everyone should supplement with magnesium – even if this is often suggested on social media.

In this article, you will learn what benefits magnesium truly offers athletes, when supplementation is advisable, and which forms are best absorbed.

Physiological Functions of Magnesium

Magnesium is the second most abundant intracellular cation (positively charged when dissolved in liquid) and is involved in hundreds of vital physiological processes. This includes:

- Energy Metabolism: Magnesium stabilizes ATP (Mg-ATP complex) and is thus essential for all ATP-dependent reactions (1)

- Nervous System: Modulates NMDA receptors and promotes inhibitory GABAergic pathways – thus dampening neuronal hyperexcitability (2)

- Muscle Function: Enables muscle relaxation after contraction and regulates calcium homeostasis (1)

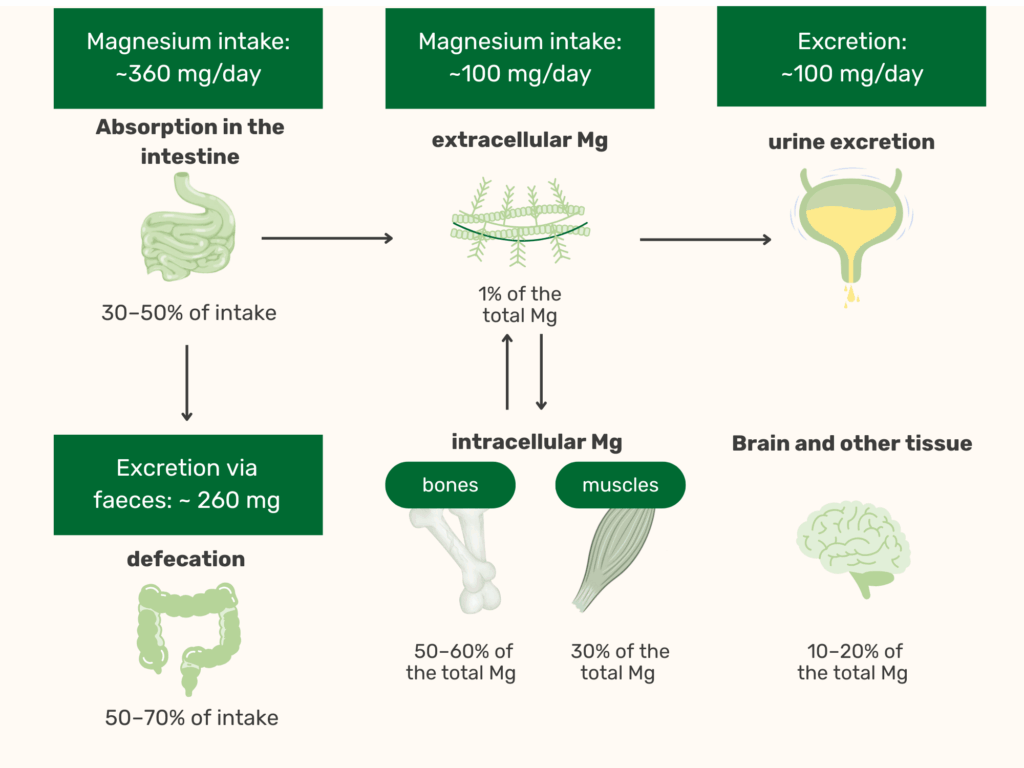

- Bone Health: Approximately 50–60% of total magnesium is stored in the skeleton, where it performs structural functions and serves as a reservoir for extracellular Mg balance (1)

- Immune and Cardiovascular System: Acts as a natural calcium channel blocker, influencing vascular tone, heart rhythm, and blood pressure (3)

Current Magnesium Recommendations from the German Nutrition Society (DGE)

The DGE recommends a daily intake of 350 mg/day for men and 300 mg/day for women (4). These values are intended to ensure the supply for approximately 97% of the population. Unlike other nutrients, these values are estimates rather than precisely calculated requirements, due to insufficient data for accurate quantification (5). Consequently, the precise requirement for magnesium has not yet been established

How are the Reference Values Established – and how should they be interpreted?

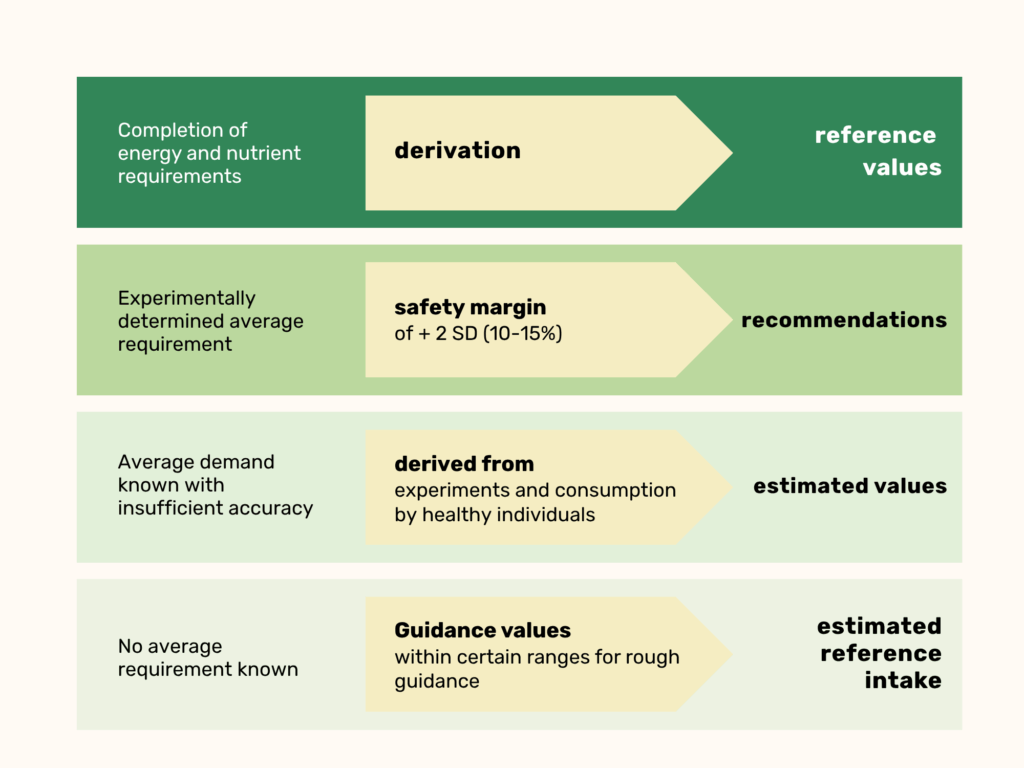

The derivation of reference values typically occurs in three steps:

- Determination of average requirements through balance studies (intake vs. excretion)

- Safety margins of 10–15% or two standard deviations to cover interindividual differences.

- Establishment of estimated values when insufficient data are available (6)

In the case of magnesium, the following aspects should be considered:

- Serum magnesium is often used as a marker, although it only reflects approximately 1% of the body’s total magnesium and can fluctuate significantly due to redistribution processes (1) – see figure.

- Many balance studies have methodological weaknesses: underreporting of intake, high variability in absorption and renal excretion (5).

- The reference values are designed to prevent deficiency rather than to optimise performance (6); therefore, potential additional benefits of higher intake levels are not taken into account.

Furthermore, the body is capable of redistributing magnesium among different tissues. For example, following exercise, magnesium is mobilized from bone stores to other tissues to compensate for losses or temporarily increased demand in those tissues (7). Consequently, changes in blood magnesium levels are of limited significance.

Magnesium status in Germany

According to national nutrition surveys, the average magnesium intake in Germany is 323 mg (men) and 237 mg (women) (8). For comparison: The DGE recommendations are 350 and 300 mg per day for men and women.

Only Approximately 27% of Men and 18% of Women Reach the DGE Reference Values for Magnesium (8).

Unfortunately, the most recent data date back to 2008, and no newer large-scale data on micronutrient supply in Germany are available.

Another factor to consider is the influence of other dietary components, such as high intakes of calcium, sodium, alcohol, phosphorus (10) or caffeine (11). These can further impair magnesium retention and thus additionally increase the requirement.

Overall, it is therefore not unlikely that the average person consumes too little magnesium. But what about athletes?

Magnesium requirements for athletes: Increased needs due to training?

On average, athletes lose approximately 1–6 mg of magnesium per liter of sweat, which appears relatively low when compared with reference intakes of about 350 mg per day. Under high-temperature conditions, higher loss rates of up to approximately 15 mg/L have been reported. (12).

Magnesium is indirectly involved in energy supply processes (glycolysis). For this reason, it is suggested that sport leads to a “faster depletion” of magnesium stores. However, the magnesium concentration in muscles actually appears to be increased after exercise, while a slight decrease in blood concentration and increased excretion via urine can be observed simultaneously (13, 14). It is now understood that the observed changes in magnesium levels across various tissues are primarily due to redistribution within the body, with magnesium being shifted to tissues where it is most urgently required. During exercise, this primarily involves skeletal muscle. (12).

Overall, it is assumed that the loss through sweat and the increased excretion of magnesium via urine increase the overall requirement by approximately 10-20% (12).

However, in this context as well, the optimal magnesium intake has not yet been established. And the previously mentioned influences, such as high calcium or sodium intake, can further increase the requirements.

Magnesium and Stress: an Underestimated Connection?

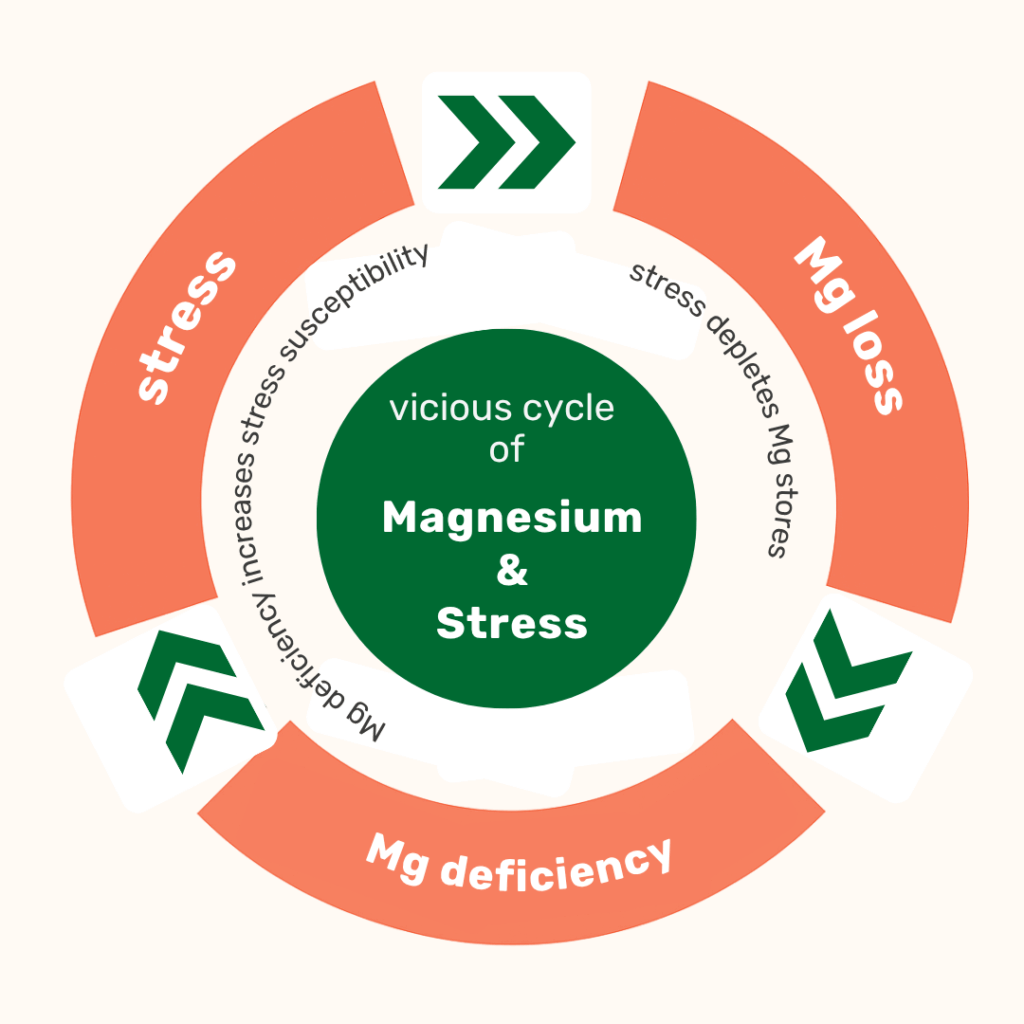

An interaction between stress and magnesium is known, though not fully understood. Both acute and chronic stress increase renal magnesium excretion through adrenaline (13). In this context, the following data are of itnerest:

- There is evidence that stress (e.g. in the form of noise) promotes the excretion of magnesium (14)

- In students, significantly increased stress levels were found after an exam phase, which correlated with a reduced magnesium concentration in the blood (15)

- Also in students, a significantly increased excretion of magnesium via urine was found during an exam phase (16)

At the same time, magnesium deficiency appears to impair stress resilience, requiring increased activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis to maintain stress regulation. (17).

Based on these connections, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Stress ➡️ Magnesium Deficiency ➡️ Stress Resistance Worsens ➡️ More Stress ➡️ Even More Magnesium Excretion.

This could potentially set up a vicious cycle between magnesium status and stress regulation (18). Unfortunately, the argument relies primarily on physiological connections, as good intervention studies are lacking

However, there is at least some additional data that provides evidence of the influence of magnesium on stress management. Clinical studies have shown that supplementation with 250–500 mg/day of magnesium in stressed individuals can lead to a significant reduction in cortisol (19) or improved heart rate variability (HRV) (20). Improved stress management and reduced anxiety and depression symptoms were also found in people with latent magnesium deficiency (21).

Unfortunately this has NOT been tested in the context of sport or in athletes. Therefore, we do not know how magnesium affects exercise-induced stress.

It is also worth noting that many studies included only small sample sizes and often did not assess magnesium status objectively at baseline. In addition, the effects in individuals with normal magnesium levels are less clear. Even so, the available data suggest that magnesium plays an important role in stress regulation and should be explored further in larger randomized studies.

Magnesium and Sleep Quality

Magnesium influences sleep on several levels:

- It was found that rat cortical synaptoneurosomes (parts of synapses responsible for signalling) respond more strongly to the GABA agonist muscimol in the presence of magnesium (22). GABA is the most important inhibitory neurotransmitter that “calms” the brain. Magnesium seems to strengthen GABA’s inhibitory effect.

- Glutamate is the main excitatory messenger in the brain. It exerts its effects through NMDA receptors, which are blocked by magnesium under resting conditions. In this role, magnesium acts like a natural “plug” that helps prevent excessive neural activity. When magnesium levels are low, this blockade becomes weaker, making nerve cells more sensitive and potentially contributing to inner restlessness, tension, and sleep disturbances. (23).

Intervention Studies

In two studies with older adults, taking 320 mg (24) and 500 mg (25) magnesium improved the subjective perception of sleep quality. Biomarkers for magnesium supply could also be improved after ingestion. Over a period of 20 days, slow-wave sleep (measured with EEG = gold standard) could be improved in seniors after magnesium intake (26). Overall, The time needed to fall asleep was reduced, sleep duration was prolonged, and overall sleep quality improved. In the EEG study (27), an increase in slow-wave sleep and a reduction in nocturnal awakenings were also observed—but only in older adults, not in healthy young individuals or athletes. For example, the improved sleep quality in older adults could potentially be due to a previously inadequate magnesium intake, which is often the case (28).

In the only study involving younger adults with sleep problems, subjectively rated sleep quality improved after 21 days of supplementation with 1 g of magnesium threonate. However, no studies have been conducted specifically in athletes, so the relevance of these findings for this target group remains unclear (29).

Magnesium and Athletic Performance

It is assumed that athletes have a slightly increased requirement of 10-20%. This is primarily due to the increased losses through sweat and the increased metabolic requirements, which lead to an increased “consumption” of magnesium, although this thesis is not yet so well documented (30).

Animal studies (31) and individual reports from athletes (32) suggest that magnesium deficiency may negatively affect muscular performance. In a small pilot study, a targeted reduction in magnesium intake in postmenopausal women led to poorer oxygen delivery and an increased heart rate.(33). The potential benefits of magnesium intake above the daily requirements for recovery or athletic performance remain unclear.

Studies on endurance athletes show that supplementation can lower blood pressure during exercise (34). Other studies report less muscle soreness (DOMS) and lower CK levels (a marker for muscle damage) after intense exercise (33), but other studies have not been able to confirm the positive observations (35). And that’s more or less all the data we currently have on the topic of “magnesium supplementation for athletes.” Overall, the evidence is weak and insufficient to draw definite conclusions. At present, there is no clear evidence that magnesium supplementation improves athletic performance in healthy athletes, particularly when adequate intake is already achieved through a balanced diet.

Bioavailability of Different Magnesium Forms

| Magnesium Compound | Properties | Studies & Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Magnesium oxide (MgO) | High proportion of elemental magnesium, but poor solubility and absorption (~4%) | Firoz & Graber (2001): [36] |

| Magnesium Citrate | Good solubility and 30–40% better absorption than MgO. Well researched; can have a laxative effect in high doses. |

Walker et al. (2003): [37] Kappeler et al. (2017): [39] |

| Magnesium Chloride, Lactate, Aspartate | Higher bioavailability than MgO. Good alternatives to citrate, but less common commercially. |

Lindberg et al. (1990): [40] |

| Magnesium Glycinate / Diglycinate | High tolerability and very good absorption. In one study, better absorption than Mg-Citrate. In another study, almost identical bioavailability. The use of peptide transporters could facilitate absorption. | Schuette et al. (1994): [41] Ashmead (2010): [42] |

| Magnesium Malate, Acetyltaurate, Sulfate | Animal studies show better tissue distribution for malate and acetyltaurate. Sulfate is often used intravenously; orally, it is strongly laxative. |

Moreira et al. (2018): [43] |

| Magnesium L-Threonate | Increases the magnesium concentration in the brain in animal models. First RCT study shows possible improvements in sleep quality. Poorer bioavailability than magnesium citrate. |

Slutsky et al. (2010): [44] Wienecke et al. (2023): [45] |

Conclusion

- Magnesium is involved in numerous important physiological processes and plays a central role in health and performance.

- However, this does not automatically mean that everyone should supplement with magnesium.

- What matters most is the balance between dietary intake and individual requirements, which may be higher during chronic stress or intense physical exertion.

- Studies demonstrate positive effects of additional magnesium supplementation primarily in connection with stress management and sleep quality – however, almost exclusively in older individuals with insufficient Mg intake.

- It is currently unclear whether regular magnesium supplementation provides additional benefits when nutrient intake is already adequate.